Peter Ma | Jan 25th 2025

Using what we have derived, let us now try and understand the birth, life and death of a star.

Birth

The birth of a star requires it to be formed from cloud of molecular gas. The reason for stars to form there is that only those clouds are large enough and cold enough to undergo gravitational collapse.

We go back to fuids to find the jeans length. \[1/k_j = \sqrt{\frac{v_s^2}{4\pi G \rho_0}} \] We can then find the mass for gravitational collpase. \[M_j = \frac{4\pi}{3}k_j^3 \rho_0\] \[M_j = \frac{4\pi}{3}(\sqrt{\frac{{v_s^2}}{ 4\pi G \rho_0}})^3 \rho_0\] \[M_j = \frac{4\pi}{3}(\frac{v_s^2}{4\pi G})^3 \rho_0^{-1/2}\] We know that the speed of sound is related to the temperature by \[v_s^2 = \frac{ kT}{\mu m_p}\] We can then find the mass for gravitational collapse. \[M_j = \frac{4\pi}{3}(\sqrt{\frac{ kT}{\mu m_p}})^3 \rho_0^{-1/2}\] \[\boxed{M_j = \frac{4\pi}{3}(\sqrt{\frac{ k}{\mu m_p}})^3 T^{3/2}\rho_0^{-1/2}}\] \[\boxed{M_j \propto T^{3/2}\rho_0^{-1/2}}\]

- Cloud Collapse: Isothermal collapse as molecular lines cool it down. Collapse on free fall time scales.

- Fragmentation: clouds collapse but collapses in slightly unevenly and triggers fragmentation as different areas trigger jeans instability at different times.

- Proto-core: As the density goes up, it becomes optically thick and suddenly is in hydrostatic equilibrum on very short timescales.

- Accreation Phase: the cloud starts to accrete onto the proto-core. This adds additional mass and heat as the gravitational potential is converted into a luminosity. Energy Source: The protostar is not yet powered by nuclear fusion. Its luminosity comes from the gravitational potential energy released as gas falls onto the core. The luminosity is given by: \(L \approx L_{acc} \sim \frac{1}{2} \frac{G M \dot{M}}{R}\) evolving on Kelvin-Helmholtz time scales.

- Molecular Disassociation and Ionization: As the cloud contracts, it heats up. However, when the gas reaches specific critical temperatures, the thermal energy is no longer used to increase temperature (pressure support). Instead, it is consumed to change the state of the matter (breaking bonds or stripping electrons). This is dynamically unstable and triggers collapse. It collapses on free fall time scales while dissociation and ionization releases heat which adds pressure support. However the process of heating up it collapses at thermal timescale and then the cycle repeats.

- Pre-main sequence phase: Because the outer layers are so opaque (resistant to radiation), radiation cannot easily transport the energy out and thus the stars are almost entirely convective. This state forces the protostar to reside on the Hayashi Line in the HR diagram—a nearly vertical line representing the region where fully convective stars in hydrostatic equilibrium must exist Any star to the right of this line (cooler) cannot be in hydrostatic equilibrium, which is why it is a "forbidden region".

Life - Main Sequence

The life of a star stays on the main sequence and burns hydrogen in its core. The Main Sequence (MS) is defined by a state of Complete Equilibrium. A star on the MS satisfies two conditions simultaneously: Hydrostatic Equilibrium and Thermal Equilibrium (This means there is no net change in the star's entropy with time).

To understand the life of a MS star requires us to solve the stellar structure equations. But we can also get out useful scalings using Homology.

Here are the stellar structure equations: \[\frac{dM}{dr} = 4\pi r^2 \rho \tag{mass conservation}\] \[\frac{dP}{dr} = -\frac{GM}{r^2} \rho \tag{hydrostatic equilibrium}\] We can have radiative diffusion or convection as the dominant energy transport. \[\frac{dT}{dr} = -4 \pi r^2 \rho [\frac{-Gm}{4\pi r^2} \frac{T}{P} \nabla_{rad}],\quad \nabla_{rad}= \frac{3\kappa }{16 \pi a c G} \frac{lm}{mT^4} \tag{radiative diffusion}\] \[\frac{dT}{dr} = -4 \pi r^2 \rho [\frac{-Gm}{4\pi r^2} \frac{T}{P} \nabla_{ad}],\quad \nabla_{ad} \Rightarrow \frac{r}{T} \frac{dT}{dr}_{ad} = \frac{1}{\gamma}\frac{\rho}{P} \frac{dP}{dr} \tag{convection diffusion}\] \[\frac{dL}{dr} = 4\pi r^2 \rho \epsilon \tag{energy production}\] We can then use homology to get the following scalings:

Homology

Homology essentially, homology treats different stars as scaled versions of each other. They assume in HE, same opacity, same EOS and such. Example mass conservation: \[\frac{dM_1}{dr_1} = 4\pi r_1^2 \rho_1 \] \[dM_1 = dM_2 \frac{M_1}{M_2} \] \[dr_1 = dr_2 \frac{r_1}{r_2} \] We can then write the mass conservation equation as: \[\frac{dM_1}{dr_1} = \frac{dM_2}{dr_2} \frac{M_1}{M_2} \frac{r_2}{r_1} \] add in the mass continuity equation \[4\pi r_1^2 \rho_1 = 4\pi r_2^2 \rho_2 \frac{M_1}{M_2} \frac{r_2}{r_1} \] \[r_1^3 \rho_1 = \rho_2 \frac{M_1}{M_2} r_2^3 \] \[\boxed{ \frac{\rho_1}{ \rho_2} = \frac{M_1}{M_2}(\frac{r_1}{r_2})^{-3}} \]

Hydrostatic equilibrium: \[\frac{dP_1}{dr_1} = -\frac{G M_1}{r_1^2} \rho_1 \] \[dP_1 = dP_2 \frac{P_1}{P_2} \] \[dr_1 = dr_2 \frac{r_1}{r_2} \] We can then write the hydrostatic equilibrium equation as: \[\frac{dP_1}{dr_1} = \frac{dP_2}{dr_2} \frac{P_1}{P_2} \frac{r_2}{r_1} \] add in the hydrostatic equilibrium equation \[-\frac{G M_1}{r_1^2} \rho_1 = -\frac{G M_2}{r_2^2} \rho_2 \frac{P_1}{P_2} \frac{r_2}{r_1} \] Simplify \[-\frac{M_1}{r_1} \rho_1 = -\frac{ M_2}{r_2} \rho_2 \frac{P_1}{P_2} \] \[\frac{ M_1}{M_2} \frac{r_2}{r_1} \frac{\rho_1}{\rho_2} = \frac{P_1}{P_2} \] We can replace density with our previous homology result \[\frac{ M_1}{M_2} \frac{r_2}{r_1} \frac{M_1}{M_2}\frac{r_2^3}{r_1^3} = \frac{P_1}{P_2} \] \[\boxed{ \frac{P_1}{P_2} = \frac{ M_1^2}{M_2^2} \frac{r_2^4}{r_1^4} }\] If we used the equation of state \(P= nkT\) we can get \[\frac{P_1}{P_2} = \frac{\rho_1}{\rho_2} \frac{T_1}{T_2}\] \[\frac{P_1}{P_2} = \frac{M_1 /R_1^3}{M_2 /R_2^3} \frac{T_1}{T_2}\] We can then replace to get \[\boxed{ \frac{T_1}{T_2} = \frac{ M_1}{M_2} \frac{r_2}{r_1} }\]

Radiative: let us look at how to get out luminosity: \[\frac{dT_1}{dr_1} = \frac{-3 \kappa \rho_1}{4 ac} \frac{1}{T_1^3} \frac{l}{4\pi r_1^2}\] Let us slowly replace everything with our homology results: \[ \frac{T_1}{T_2} = \frac{ M_1}{M_2} \frac{r_2}{r_1} \] \[\frac{dT_1}{dr_1} = \frac{-3 \kappa \rho_1}{4 ac} \frac{1}{(T_2 \frac{ M_1}{M_2} \frac{r_2}{r_1})^3 } \frac{l}{4\pi r_1^2}\] more homology results \[\frac{\rho_1}{ \rho_2} = \frac{M_1}{M_2}(\frac{r_1}{r_2})^{-3}\] place it in \[\frac{dT_1}{dr_1} = \frac{-3 \kappa \rho_2 \frac{M_1}{M_2}(\frac{r_1}{r_2})^{-3}}{4 ac} \frac{1}{(T_2 \frac{ M_1}{M_2} \frac{r_2}{r_1})^3 } \frac{l}{4\pi (r_2 \frac{R_1}{R_2})^2}\] \[\frac{dT_1}{dr_1} = \frac{-3 \kappa \rho_2 }{4 ac} \frac{1}{ ( \frac{ M_1}{M_2})^{2}T_2 } \frac{\frac{l_1}{l_2}}{4\pi (r_2 \frac{R_1}{R_2})^2}\] \[\frac{dT_1}{dr_1} = (\frac{ M_1}{M_2})^{-2} (\frac{ r_1}{r_2})^{-2}\] We replace the derivative: \[\frac{dT_1}{dr_1} = \frac{dT_2}{dr_1} \frac{T_2 (\mu1/\mu2) (M_1/M_2)(R_2/R_1)}{r_2 R_1/R_2} = \mu (M_1/M_2) (R_2/R_1)^2\] Now we figure out the right side: \[\boxed{\frac{l_1}{l_2} \propto (\frac{m_1}{m_2})^{3} \mu_1^{4} \mu_2^{4}}\] If you add back krammers opacity you get \[\]

Death - post main sequence

Big picture Death:

1. The Dividing Line: Degeneracy Pressure

The key event in a star's late life is whether its core crosses the boundary of electron degeneracy in the temperature-density plane .

- If it crosses: The core becomes supported by electron degeneracy pressure. This pressure is independent of temperature, so it stops the contraction and prevents the core from heating up further to ignite the next fuel (e.g., Carbon). The star dies as a White Dwarf .

- If it never crosses: The core continues to contract and heat up, igniting successively heavier elements (C, Ne, O, Si) until it forms an Iron core and collapses/explodes .

2. Low and Intermediate Mass Stars (M < 8 M☉)

These stars end their lives as White Dwarfs (WDs) because their cores become degenerate before they can fuse Carbon .

- Very Low Mass (M < 1 M☉):

- They never get hot enough to ignite Helium.

- End Result: Helium White Dwarf .

- Low Mass (1 < M < 2 M☉):

- They develop a degenerate Helium core.

- Helium ignition happens explosively via a "Helium Flash" .

- Eventually, they build a Carbon/Oxygen core that becomes degenerate.

- End Result: Carbon/Oxygen (CO) White Dwarf .

- Intermediate Mass (2 < M < 8 M☉):

- They ignite Helium gradually (non-degenerately) .

- They build up a C/O core which eventually becomes degenerate.

- End Result: Carbon/Oxygen (CO) White Dwarf .

3. Massive Stars (M ≥ 8 M☉)

These stars are massive enough that their cores remain non-degenerate during contraction.

- They ignite Carbon and proceed through heavier nuclear burning stages.

- End Result: They ultimately explode as supernovae, leaving behind a Neutron Star (NS) or a Black Hole (BH) .

4. The White Dwarf Graveyard

For the vast majority of stars (the low/intermediate ones), the final state is a White Dwarf, which is described in Lecture 22 as follows:

- Structure: They consist of a degenerate electron core (providing pressure) and a thin non-degenerate envelope (insulating the core) .

- Cooling: Since they have no nuclear fuel, they shine by radiating away their stored thermal energy (from the ions, not electrons). They simply cool down and fade over billions of years .

- Mass Limit: They cannot exceed the Chandrasekhar Mass (≈ 1.4 M☉), or they would become dynamically unstable .

White Dwarf

White dwarfs are the final stage of stellar evolution for stars with masses less than 8 \(M_\odot\). And they are unique in that they are supported by electron degeneracy pressure rather than thermal pressure.

Let us find how the radius and mass scale with each other. We start with the hydrostatic equilibrium equation: \[\frac{dP}{dr} = -\frac{Gm}{r} \rho\] \[\frac{P}{r} \sim -\frac{Gm}{r} \rho\] \[P \sim -\frac{Gm^2}{r^4}\] \[P \sim K \rho^{5/3} \tag{EOS degenerate NR}\] plug in for density \[P \sim K M^{5/3} \frac{1}{R^5} \] \[ -\frac{GM^2}{r^4} \propto K M^{5/3} \frac{1}{R^5}\] \[ -\frac{G}{r^4} \propto K M^{-1/3} \frac{1}{R^5}\] \[\boxed{R \propto M^{-1/3}}\] Chandrasekhar Limit: given by when equation of state goes relativistic and is dynamically unstable. \[P \sim K M^{4/3} \frac{1}{R^4} \] \[ -\frac{GM^2}{r^4} \propto K M^{4/3} \frac{1}{R^4}\] We see that radius cancels out and we get just a mass relation: \[\boxed{M \propto (K/G)^{3/2} \sim 1.44 M_\odot}\]

Temperature and Luminosity relation The White Dwarf has a highly conductive, isothermal core (at temperature \(T_c\)) wrapped in a thin, non-degenerate, radiative envelope. The luminosity is determined by how easily heat can leak through this opaque envelope. \[\frac{dP}{dr} = -\frac{Gm}{r^2} \rho\tag{hydrostatic equilibrium}\] \[\frac{dT}{dr} = \frac{-3\kappa \rho}{16 \pi ac} \frac{L}{4\pi r^2T^3} \tag{radiative diffusion}\] We divde the two equations to get: \[\frac{dT}{dP} = \frac{\kappa L}{MT^3}\] bring in the opacity from kramers opacity law: \[\kappa \propto \rho T^{-7/2}\] \[\frac{dT}{dP} = \frac{L}{MT^{17/2}}P\] We integrate \[\int T^{17/2}dT = \int \frac{L}{M}PdP\] \[\frac{2}{19}T^{19/2} = \frac{L}{M}P^2\] \[\frac{2}{19}T^{19/4} (\frac{L}{M})^{-2}= P\] We can drop in ideal gas law \[\rho \propto \frac{P}{kT}\] \[\rho \propto \frac{\frac{2}{19}T^{19/4} (\frac{L}{M})^{-2}}{T}\] At the core the equation of state needs to match \[P = kT = \rho^{5/3}\] together we get that: \[\boxed{L \propto M T^{7/2}}\]

Cooling time: since there is no energy production, the white dwarf will cool down via radiative diffusion.

Total energy stored: \[U = MT\] We also know that the temperature luminosity relation is: \[L\propto T^{7/2}\] \[L^{2/7}\propto T\] And we know that \[L = \frac{dU}{dt}\] We rewrite \[\] \[L = M\frac{dT}{dt}\] \[L = M\frac{dL^{2/7}}{dt}\] \[L = ML^{-5/7}\frac{dL}{dt}\] \[dt= ML^{-5/7}\frac{dL}{L}\] \[\int dt= \int ML^{-12/7}dL\] \[\boxed{t\propto ML^{-5/7}}\]

Massive Stars \(M > 8 M_\odot\)

Massive stars continue to fuse Helium into larger more massive elements. At the end of its nuclear burning sequence, a massive star develops an "onion skin" structure with layers of progressively heavier elements, ending with an Iron (Fe) core in the center. Iron cannot fuse to release energy; instead, fusion would consume energy.

Photodisintegration: Iron is broken up into smaller nuclei. This process is endothermic (absorbs heat), drastically reducing the core's thermal pressure. Changes the adiabatic index to 4/3 and becomes unstable.

Inverse Beta DecayElectron Capture: Due to high densities, electrons are forced into protons to form neutrons and neutrinos. And looses degeneracy pressure.

Free fall: With pressure support gone, the core collapses under gravity on a dynamical timescale free fall.

The Bounce: The collapse continues until the core density exceeds nuclear density. At this point, the strong nuclear force becomes repulsive (the Equation of State goes back to 5/3), causing the inner core to rebound or "bounce".

Shock:This bounce generates a big shock wave that moves outward.

Stalling: As the shock moves through the outer iron core, it loses energy by dissociating heavy nuclei, causing it to stall.

Neutrino Revival: The collapsing core releases a massive burst of neutrinos. These neutrinos deposit some of their energy into the stalled shock layer, reheating it and "reviving" the shock.

Key Calculations: Energetics of the core: \[\Delta E = GM_c^2/R_c \sim 10^{53} ergs\] Energy of the shock: \[\Delta E = \frac{1}{2} M_c v_s^2 \sim 10^{51} ergs\] Energy of the neutrinos should be carying away the result which is \(99\%\) of the energy. The neutrinos are fromed via inverse beta decay and electron capture.

Neutrino Trapping: We find the cross section for neutrino scattering and then find the mean free path to see that the core would be too dense and thus traps the neutrinos in it.

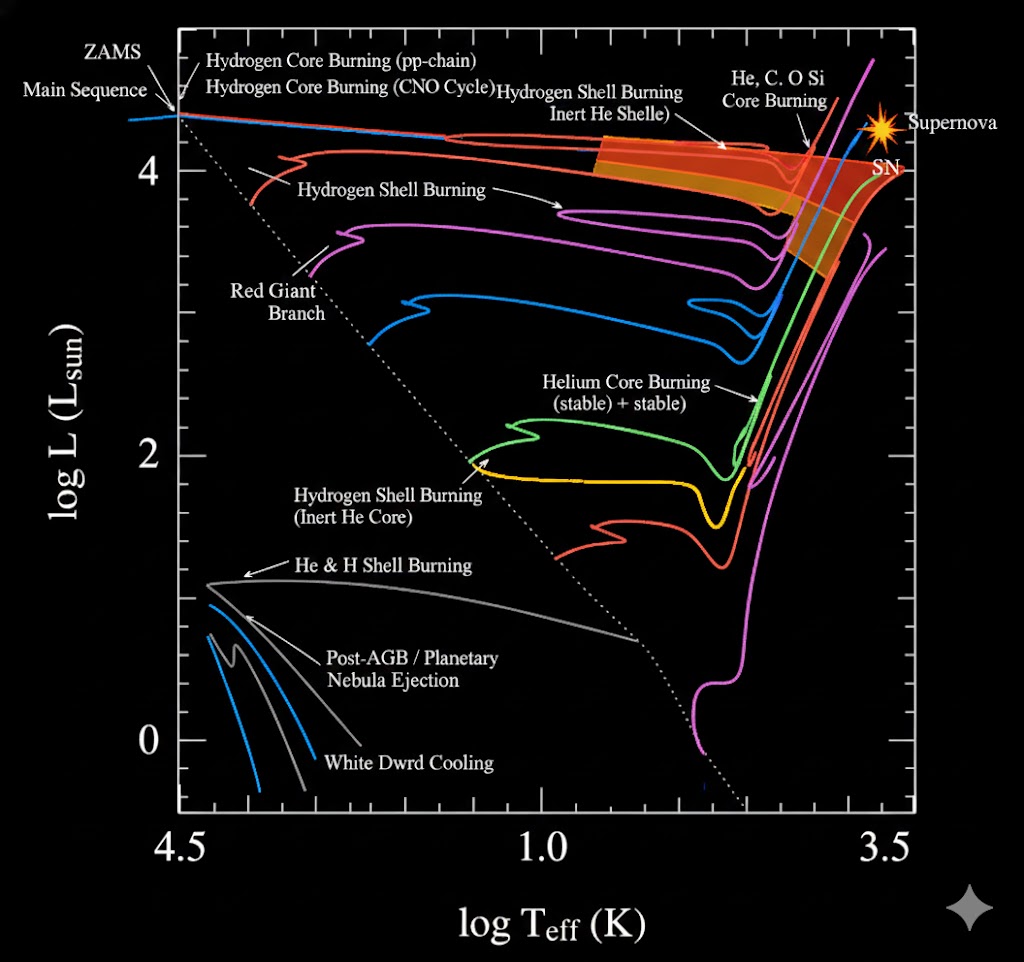

All Together Now:

Now having captured the essential elements, we can now plot their lives on the HR diagram and the temperature density plot.

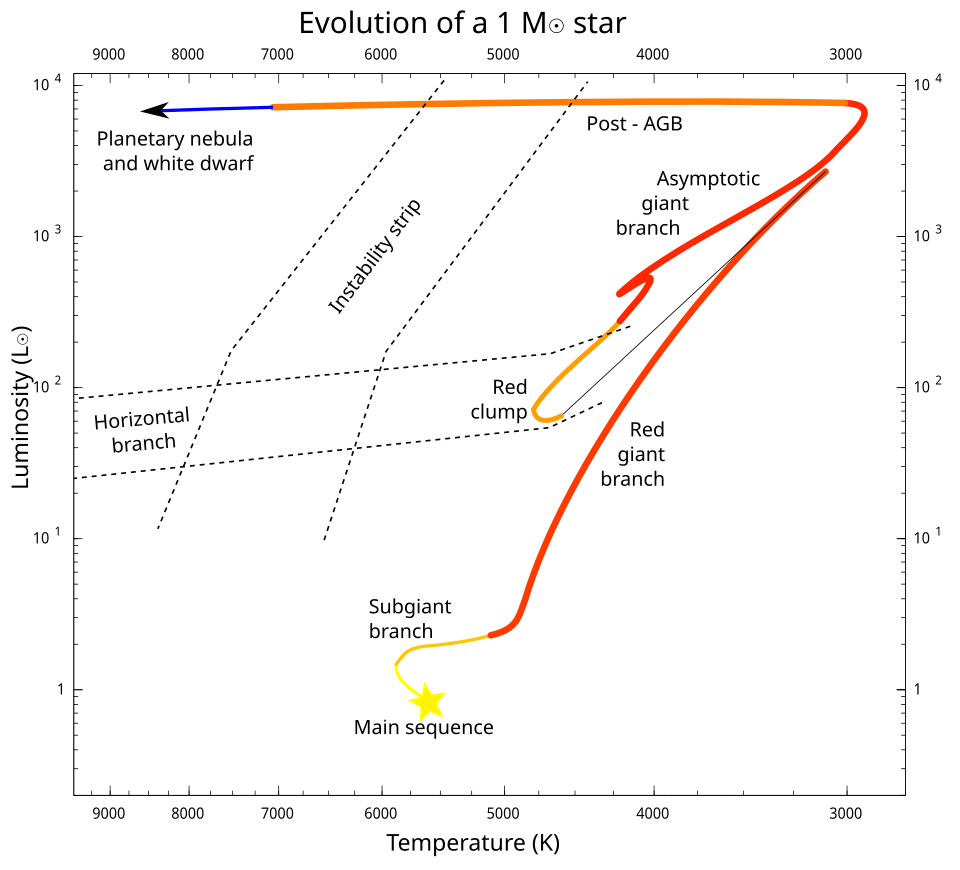

Low Solar Mass Stars: \(<2 M_\odot\) These stars end up as Carbon/Oxygen white dwarfs. When they are born they are on the main sequence.

As as they burn up their hydrogen core they migrate off the main sequence in the Sub Giant Branch (horizontal line). This is because they start burning hydrogen in the shell dumps heat into the envelope causing it to expand. Cooling it. \(T \downarrow\) but it gets larger \(R \uparrow\). The total luminosity \(L \propto R^2T^4\) stays flat.

Then it goes vertical. As it continues to cool, eventaully recombination kicks in and opacity \(\kappa \uparrow\). This kicks in convection bringing it into the red giant branch. Here it is stuck at the Hayashi line (fixed temperature because recombined hydrogen locks in the temperature) and can only release the energy by getting physically larger \(L \propto R^2\). This entire process dumps more and more helium into the core.

Then it will reach a luminosity limit where it ignites helium fusion. However these would've passed the density threshold for degenerate helium creating a unstable reaction Helium Flash. This continues until the temperature rises to lift degeneracy.

Now it is burning helium at the core and is stable and calm and doesnt move much (red clump).

AGB (Asymptotic Giant Branch) After fusing to carbon and oxygen it triggers a hydrogen and helium shell burning. Core contracts. This repeats the same process of being convective and expanding and releasing more energy while at the same temperature. This chaos creates pulsations to which the star blows away its outer layers to become a white dwarf.

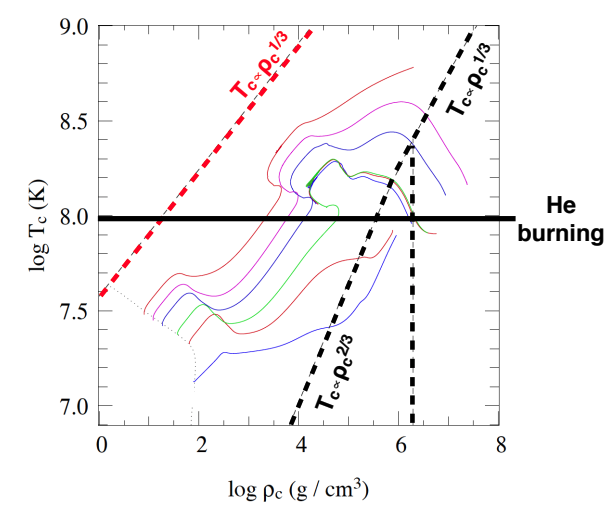

Now let us focus on the temperature density plot. The same story applies here. When the star is born it is at one particular place on the plot. When it evolves off the main sequence it moves up and to the right in the non-degenerate non-relativistic regime.

Eventually it will reach and cross the line of degeneracy. They reach the line of degenarcy. This is because hydrostatic equilibrium giving us a \(T_c \propto M^{2/3} \rho_c^{1/3}\) and so eventually for a fixed mass it will shoot a straight line and cross the steeper \(T \propto\rho^{2/3}\) line. This is different than a massive star where they start off at higher temperatures and thus their line does not intersect and fly past the slope.

Within the degenerate regime, the temperature still rises as it is burning in the shell, then it will reach helium ignition temperatures and start burning helium in degenerate mode. triggering helium flash.

The core then it forms a red clump and is stable, before running out of helium and core shrinks but isnt massive enough to ignite carbon it keeps getting denser and crosses degeneracy again.

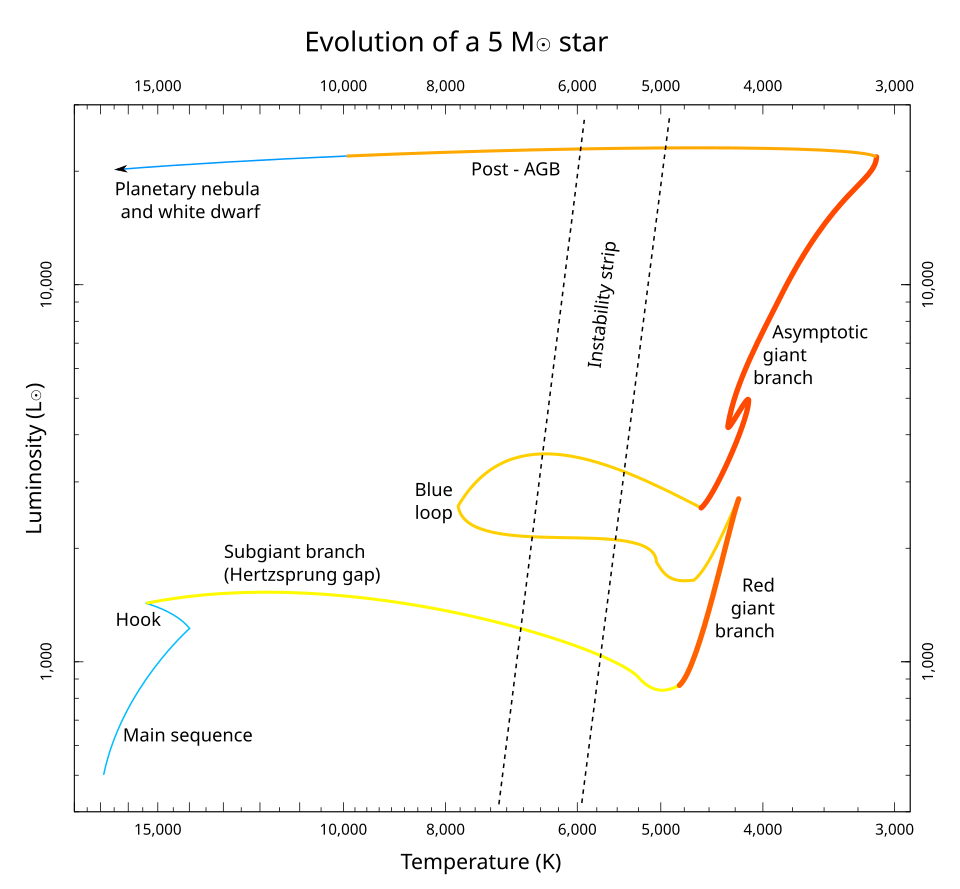

Massive Stars: \(>8 M_\odot\): Now let us take a look at big massive stars. The massive stars evolve initially similarly. They also have a sub giant branch and also have a red giant branch. However they never trigger helium flash because it never crosses the line of degeneracy. And fuses helium no problems. This creates that blue loop.

Since they fuse heavier elements there are multiple loops due to different elements at the core. Each time they follow similar process, it goes from core burning to shell burning which contracts the core and as more material is deposited the core gets hotter which triggers fusion of that heavier element etc etc...

For heavier stars eventually they run out of fuel to fuse and trigger a supernova explosion!

Looking at the temperature density plot we see that since they start off at a higher temperature they just go past up the line of degeneracy and never crosses it. It never enjoys the degeneracy pressure to keep it stable and has to fuse heavier and heavier elements until it explodes because gets a core collapse SNE.